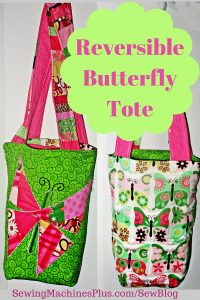

I have been making lots of bags lately, and I have a few tutorials and different bag patterns coming up here soon. This week, though, I’m showing a couple examples of butterfly bag and another variation of a simple tote bag purse.

First, I used my crazy patch butterfly appliqué blocks to make two different sizes of bags recently.

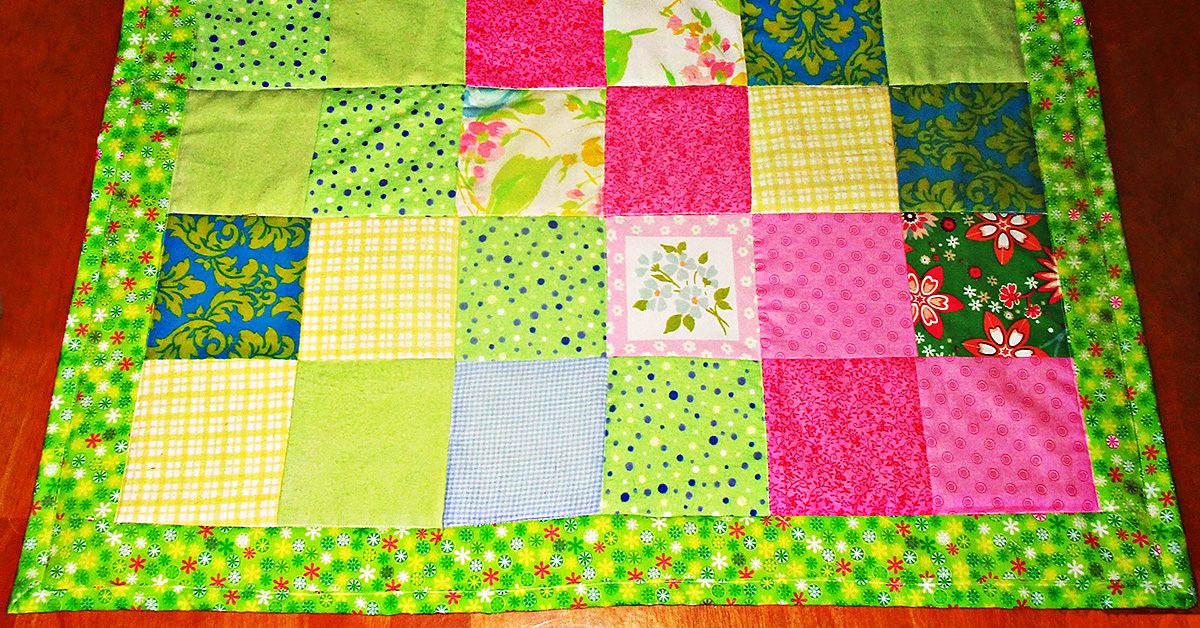

I made a butterfly bag tote as a gift for my niece’s sixth birthday. It’s a reversible tote big enough to carry coloring books and crayons to the ball park, where her brother plays nearly every day. There’s also room for a small quick quilt I made that she can use to sit on the bleachers or the ground while she’s there.

Here are the step-by-step instructions for making a reversible tote like this. You can use the strip piece method linked as a video below for making the patchwork straps.

Butterfly bag small purse

Then I found a single stray rainbow strip pieced block at the bottom of my scrap bin and I decided to make a small denim bag with a butterfly, too.

I used a rainbow variegated thread in the needle for the butterfly appliqué and also the strap and topstitching for this bag. This is probably my favorite decorative thread, and I have used it in a lot of projects.

To show off the lining fabric, I sewed the bag and lining together without straps, then folded over the top. I sewed the strap to the outside, with the raw edges under the fold. Then I used two rows of topstitching around the whole bag. I made the strap with a wider blue and narrower green piece of bias tape, covered by wide zigzag stitches up and down about five times.

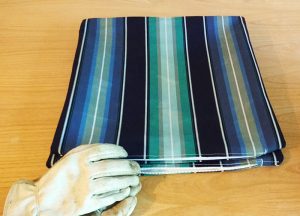

Blue patchwork tote purse

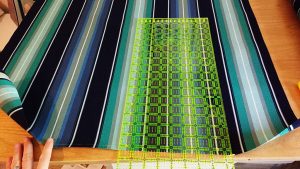

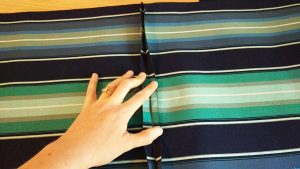

Here is a purse I made for myself last week. It is just a simple tote with the addition of a curved, bias- edged flap at the top. I quilted the patchwork using horizontal rows of a wavy decorative stitch that reminds me, like these blue fabrics, of the ocean.

To make the flap, just quilt together a rectangle of patchwork with batting and your lining fabric. Make it about an inch narrower than one side of the bag. Then you can fold it in half and cut the corners into curves. Then bind the curved edge and short ends with bias binding.

I used half of a thick turquoise ponytail elastic and a half-ball style button for a closure. I just sewed down the elastic to the lining side of the flap when I attached the bias edging. It also has a large zippered pocket inside, with patch pockets for cards inside that larger pocket.

Just baste the flap to the bag, and then tuck it between the bag layers when you sew the bag and lining together.

If you don’t know how to make this strip style patchwork, which I also used for the straps on the large butterfly tote above, here’s a video of me explaining how to do this.

I actually made this piece of patchwork some time ago. The blue quilt pattern I showed here was for my baby’s crib, and I made bumper pads, too. We didn’t really use these, so I decided to reuse the patchwork to make bags. This is the first one I have done; I plan to do a bigger laptop tote or backpack with the next one.

Like Amish quilts, these bags include mistakes!

I have to say that each one of these bags includes some little issue that I am not happy with. For example, the lining I chose for my blue bag is a gorgeous midnight blue print. But, especially with the flap, too, it is pretty impossible to see what’s in my bag without shining a light. It’s not a huge issue, since I usually just stick my hand in my bag and grab what I need by feel, anyway.

I boxed the corners too deeply on my niece’s butterfly tote and gave it a different shape than I intended. But this worked out, because the unintended bucket shape of the bag is what inspired me to make the quilt that I otherwise might not have included with this gift. And while I probably won’t ever make a strap like the one I made for the rainbow butterfly bag again, it is interesting and different looking and it works just fine.

The Amish include mistakes in their quilts on purpose. My mistakes were more accidental. The thing is though, all these little issues are lessons learned. I’ll never use a dark fabric as a bag lining again. Maybe I’ll make a post about more of these kinds of lessons I have learned the hard way soon. I’d be happy to save someone from making some of these mistakes.