My first long-term professional job in a Costume Shop was at The Alley Theatre in Houston, TX. The Alley has two stages and puts on a creative and diverse season of plays, often mounting the regional premieres of new productions. I certainly never intended to live in Texas for as long as I did but I spent my 20s at The Alley. The Alley is where I grew up and where I learned the basis for pretty much everything I know about sewing and pattern making.

Family

Years later, I was having a conversation with some friends and co-workers about our professional backgrounds. One of them asked me if I was still friends with the people I knew when I worked there.

“Friends?” I said, “They’re family.”

Then I got to thinking about family and home, mentors, and the sense of ‘belonging’ somewhere, of finding your people. Sewing is often a solitary activity. In fact, I spend most of my time these days in my little windowed corner at Steiner Studios sewing and patterning by myself. Some days, I miss being in a shop with others, everyone working and creating together.

There were days at The Alley when we would all be bent over our machines or projects, working diligently and quietly. Sometimes there was music playing, sometimes NPR (there weren’t podcasts yet), then suddenly, from the silence, someone would say, “Ummm…do we have any more of this fabric?” And everyone would burst out laughing. Ha. Tailor humor.

Nothing Beats Experience

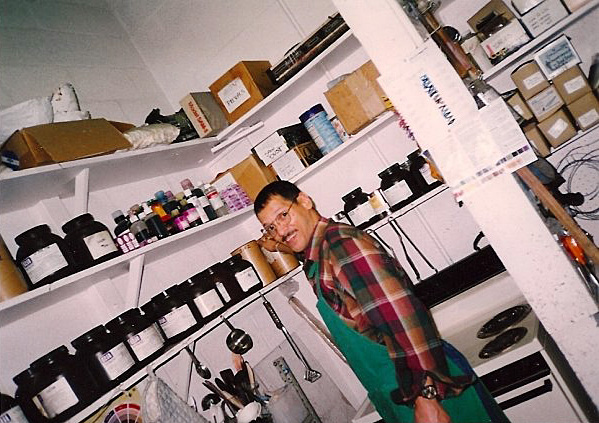

The thing, or person, I miss most from those years in theatre, though, was my mentor, Jorge, the man who taught me patterning, millinery, and gave me to courage and tools to think outside the box and trust my instincts.

I don’t have a degree in any sort of Costuming or Fashion Design and I only ever took one sewing related class at college. Lots of people I know follow patterning or draping guidelines from a particular book. I don’t dispute that many of these books are extremely useful with their formulas and precise calculations (I own and reference many of them) but I always like to say that I pattern from the heart. I know that sounds dorky but that’s the way I work. Pretty much ten times out of ten I end up at the same result as I would if I had followed some directions in a book.

And, yes, I have tested this theory many times.

The point, I think, that I’m trying to make is that the books are useful but they only tell you the how, not the why. I always want to know the why. I believe that once you figure out why something needs to be done a certain way or why that curve should look like that, the how easily follows. I also believe wholeheartedly in mentors. I think our country and society is sorely lacking in that arena. Here’s a great paper about the importance of mentors.

My Mentor

One of the best and lasting gifts I’ve ever received was Jorge’s knowledge. I am his legacy. I hope that in my approaching old(er) age I will be able to give back and share his knowledge which has become my knowledge to someone young and just starting out. In this way, he, and eventually me, will continue to live on. How humbling to think that I might have a legacy to leave.

Teach someone, even if it’s just one someone, the things you know and have learned through the years. Before books and computers, people passed their stories and knowledge to their children who passed them to their children and so on and so forth. Create your own legacy. The knowledge and talent you have so worth passing on.

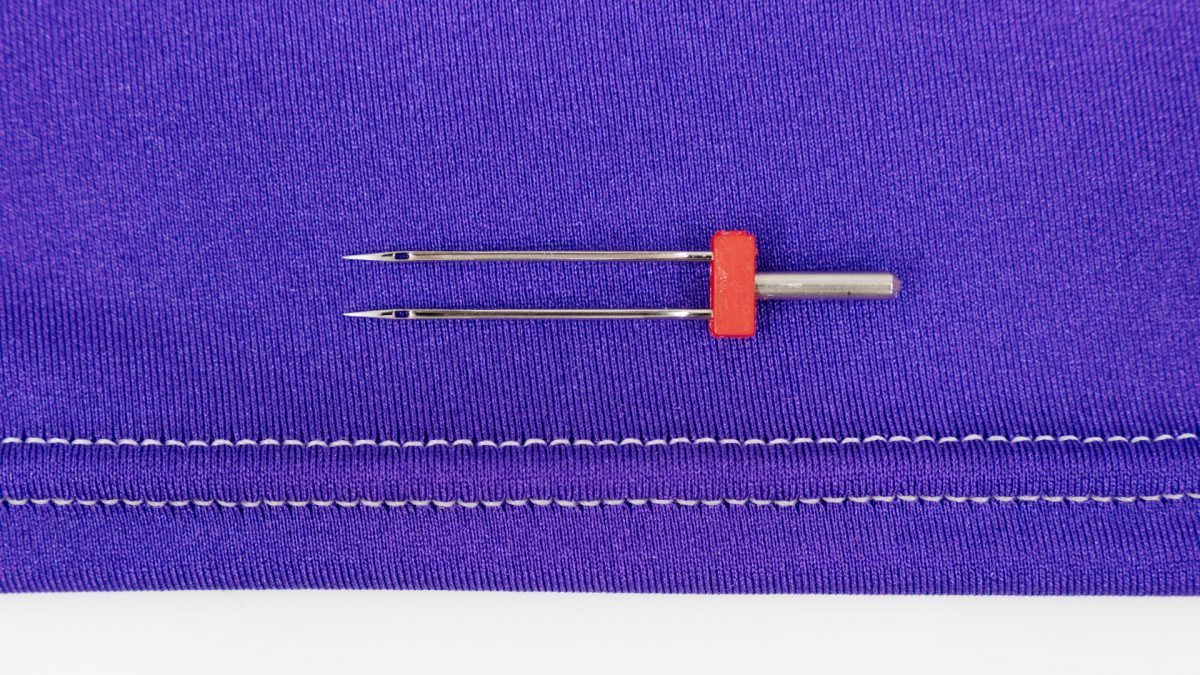

Jorge has been gone from this world for over ten years now but every single time I am unwinding a bobbin because I need an empty one and its less than halfway full, I hear his voice in my head, “Are you going to save that thread?”

And often, I do. I wrap it around a manila card because you never ever know when you might need a bit of bright green thread.